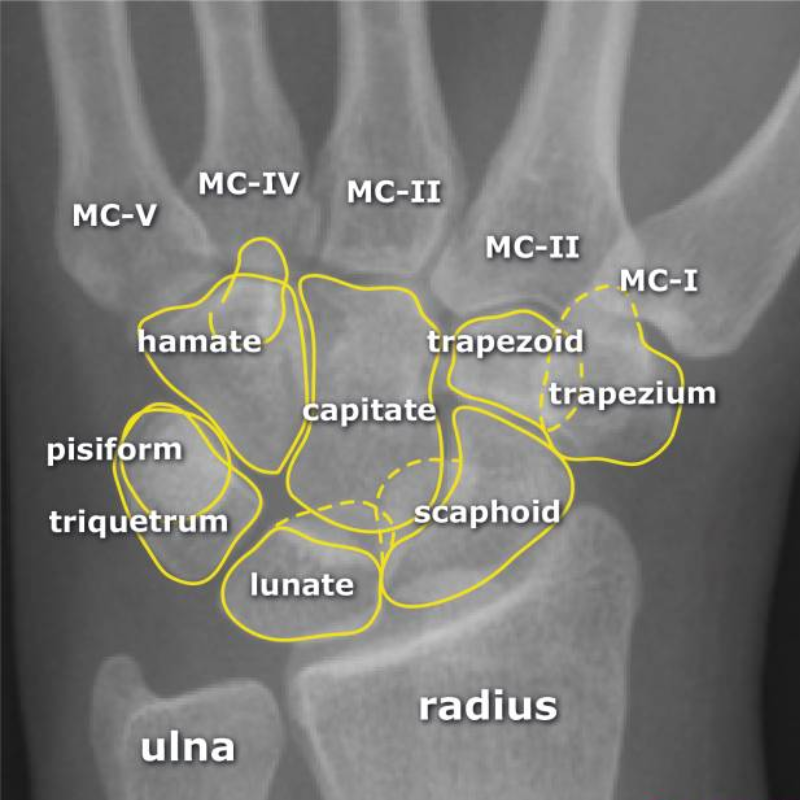

Carpal Bones

The carpal bones are a group of eight small bones that form the wrist, arranged in proximal and distal rows. Their unique anatomy and positioning influence both the likelihood of fracture and the clinical presentation. Below is an overview of each bone and its fracture frequency, along with clinical considerations.

Anatomy and Frequency of Carpal Fractures

Scaphoid – The most commonly fractured carpal bone (40–70% of cases). Its position spanning both rows of the carpus makes it vulnerable, particularly from falls onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH). Delayed diagnosis is common due to subtle symptoms.

Lunate – Very rare (0.5–1%) due to its protected position in the proximal carpal row. Lunate fractures may be confused with lunate dislocations, which carry a high risk of median nerve compression.

Capitate – Rare, owing to its central, well-protected location. Capitate fractures often occur with high-energy trauma and may be associated with perilunate injuries.

Trapezium – Accounts for 4–5% of carpal fractures. Often related to direct trauma at the base of the thumb, sometimes linked with first metacarpal fractures.

Trapezoid – Extremely uncommon (0.5–1%). Its deep position between neighboring bones provides natural protection.

Triquetrum – The second most common carpal fracture (4–18%). Typically caused by avulsion or impaction forces. May be associated with dorsal wrist pain.

Hamate – Roughly 2% of carpal fractures. The hook of the hamate is particularly vulnerable, often injured in sports such as golf, baseball, or tennis when equipment strikes the ground.

Pisiform – Rare, representing <1% of carpal fractures. Often results from direct trauma to the hypothenar region.

Clinical Presentation

Pain and swelling around the wrist, often localized to the injured bone.

Reduced grip strength or difficulty with wrist movements.

Tenderness on palpation (E.G., anatomical snuffbox tenderness in scaphoid fractures).

Possible nerve symptoms (E.G., median nerve compression in lunate injuries).

Diagnosis

Clinical examination remains crucial, especially in scaphoid injuries, which may not appear on initial X-rays.

Radiographs (standard wrist series, scaphoid views).

CT or MRI may be required for occult or complex fractures.

Treatment Overview

Immobilization – Many stable fractures (E.G., nondisplaced scaphoid, triquetrum) are treated with casting or splinting.

Surgical fixation – Indicated for unstable, displaced, or high-risk fractures (E.G., proximal pole scaphoid fractures, hook of hamate).

Rehabilitation – Early physiotherapy is essential after immobilization to restore range of motion and strength.

Summary

Carpal bone fractures, though often small and subtle, carry significant clinical implications if missed. The scaphoid and triquetrum are the most commonly injured, while other bones are rarely fractured due to their protective positioning. Prompt recognition, appropriate imaging, and timely management are key to preventing long-term complications such as nonunion, arthritis, or chronic wrist pain.